|

|

Review by Mike Bracken |

|

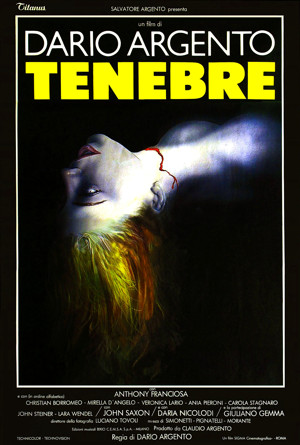

TENEBRE- 1982USA Release: Feb. 17, 1984 Sigma Cinematografica Roma / Anchor Bay Entertainment Rating: Finland & Sweden: BANNED / France: 16 / USA: Unrated |

|||

There's a scene in the film TENEBRE where the main character, Peter Neal, says, "All detection is boring. But, if you cut out the boring bits and keep the rest, you've got a best-seller." That's what director Dario Argento (PHENOMENA, SUSPIRIA, INFERNO, OPERA) has done with this film - removed the boring detective work and given us a ripping good mystery that doesn't always make sense, but never fails to entertain.

Anthony Franciosa (DRACULA IN THE CASTLE OF BLOOD, DEATH WISH 2) plays Peter Neal, a best selling mystery novelist. While in Rome to promote his new book, Tenebrae, several savage murders are committed - each inspired by the killings in the novel. Neal, with the help of Detective Germani (Giuliano Gemma: MAN IN THE SILVER SADDLE) his secretary Anne (Daria Nicolodi: PHENOMENA, INFERNO, OPERA, DEEP RED) and a teen aged boy Gianni (Christian Borromeo: MURDER ROCK, HOUSE ON THE EDGE OF THE PARK) decides to solve the murders himself . . . with frightening and unforeseen consequences.

Released in 1982, TENEBRE marked Argento's return to the giallo film, the form that started his career (see my PHENOMENA review for a brief overview of the Italian giallo subgenre) and launched him toward international fame as an iconic autuer often referred to as "Italy's Hitchcock". The film was a departure from his two previous works, SUSPIRIA and INFERNO, both of which were parts of his supernaturally-themed "Three Mothers" trilogy (the third movie in that series remains unmade at this time.) The story behind TENEBRE's conception is an interesting one.

In 1980, Argento was in L.A. to pitch a different film to MGM Studios. He was staying in a local hotel when he got a call from someone who had seen SUSPIRIA. The call was innocent enough, with the caller professing to have really enjoyed the film. The next day, the individual called Argento again, wanting to meet him so they could discuss the film. Argento declined to meet the caller. Soon after, the person called again, this time threatening to kill Argento. Dario went to the police, who concluded that it was a crank. The caller continued, even going as far as telling Argento that he knew the police were involved and that he'd have the director's skin anyway. From this incident, the central part of TENEBRE's story - the artist whose work inspires murder as homage - was born.

Argento didn't stop there, though, and for that reason TENEBRE comes across as perhaps his most personal film. At two different points in the movie, Neal is confronted with the inherent sexism and perversion in his work. First, shortly after arriving in Rome, he's attacked by Tilda, a lesbian journalist, who wonders why he continues to write books with women as murder victims and ciphers . . . books full of hairy macho bullshit. Later, when appearing on an afternoon talk show, the host wants to discuss the madness and misogyny in Neal's works. It's as if Argento were answering his own critics through the character of Peter Neal. It certainly gives the film a fascinating subtext.

In another scene open to interpretation, a victim's arm is chopped off with an ax. The spurting geyser of blood splatters the pristine white wall behind her, leading the viewer to wonder if this is Argento's way of saying, "This is my art, and regardless of what society thinks of it, there's an inherent beauty to it nonetheless."

TENEBRE also features what is Argento's most linear narrative to date. The plot follows a fairly logical progression without much of the surrealism that filled films such as SUSPIRIA and INFERNO. The first forty-five minutes of the film are especially good, setting up the mystery that Neal will later unravel.

Still, what would an Argento film be without some weird imagery? In TENEBRE, it's supplied through a series of flashbacks, in which several young boys watch as a woman in red heels strips on the beach. When one of the boys slaps her, the others begin to beat him and the woman forces her heel into his mouth. Later, the girl is stabbed in a garden, a scene which we see from the killer's perspective. The flashbacks are handled well, with each one beginning or ending with a tight shot on a wide-open iris. The scenes themselves play out in a hazy, dream-like manner, punctuated by Claudio Simonetti's odd carnival music.

The film features an overt sexual tension throughout, moreso than any of Argento's other films, with the possible exception of THE STENDHAL SYNDROME. This stands out in stark contrast to the rest of the movie's cold, clinically detached nature.

TENEBRE showcases some fine performances, especially those of Franciosa, Gemma, Veronica Lario (who has a small role as Neal's ex-wife), and genre veteran John Saxon (BLACK CHRISTMAS, A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET, A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET 3, CANNIBAL APOCALYPSE, FROM DUSK TILL DAWN) who plays Neal's agent, Bullmer. It's hard to gauge Nicolodi's performance, since her lines were dubbed in by Theresa Russell to make her more understandable. Also, keep an eye open for former Argento assistant directors Lamberto Bava and Michele Soavi, both of whom turn up in small parts throughout the film.

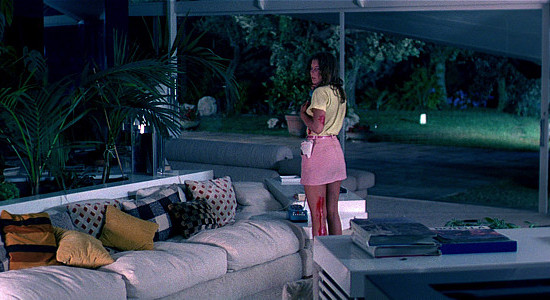

As is generally the case in an Argento movie, the production values are high. The film is set in Rome, but Argento never shows us any of the famous landmarks, in essence making it a Rome the viewer is only vaguely familiar with. Lighting also plays a vital role, with most of the scenes taking place in either broad daylight or in cold, sterile, brightly-lit rooms. This is quite a change from SUSPIRIA and INFERNO, two films noted for their lurid and garishly lit sets, and makes for an interesting visual juxtaposition when one considers that "tenebre" means darkness.

Argento manages to pull off some incredible shots, including a long Louma crane sequence where the camera pans over an entire house in intimate close-up before showing the killer sneaking in through a window. It's an impressive sequence mainly because it's done in one continuous take with no cuts, despite the fact that it adds nothing to the story.

Another great sequence is where one character stands directly in front of another. Only when the first character bends down to retrieve a handkerchief from the floor do we see the killer behind him. Brian De Palma would later utilize this same setup in his film RAISING CAIN.

Claudio Simonetti, Fabio Pignatelli, and Massimo Morante (performing under their individual names instead of the Goblin title) provide the film's heavy synth score, which accentuates the murder sequences brilliantly. Argento wouldn't start using Heavy Metal tunes in his score until PHENOMENA, and TENEBRE stands as a shining example of how a film could be more effective and less dated without them.

Giovanni Corridori's (ZOMBI 2) FX are good for the most part, particularly the severed arm, an ax to the head, and an impalement. The film also boasts several knifings, a few razor murders, a self-inflicted throat slashing, and a strangulation . . . more than enough to keep the average gore fan satisfied.

Like PHENOMENA, TENEBRE was originally released in the US with a different title (UNSANE) and cut by more than 10 minutes (including one seminal gore sequence and ending with a re-worked pop tune that neither Argento nor Simonetti approved.) Thanks to Anchor Bay, American audiences can now see the film in its uncut form, just as Argento intended. Avoid seeing UNSANE at all costs.

As it stands, TENEBRE marks the triumphant return of Argento to the subgenre that started his career. It's a powerful film that's perhaps the greatest giallo ever made, and despite the fact that it's not a flawless film, it is a movie that every horror fan should see. Because of that, I give it 5 shriek girls.

This review copyright 1999 E.C.McMullen Jr.

|

| DRESS NICE | |

| YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY (Sub-Section: PSYCHO KILLERS) |

||

|

|

|

| SE7EN MOVIE REVIEW |

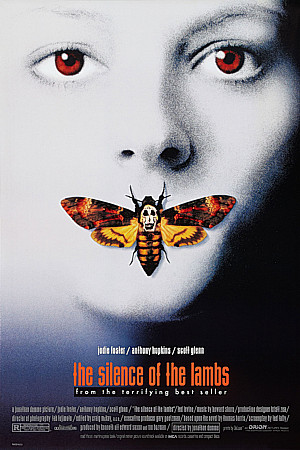

THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS MOVIE REVIEW |

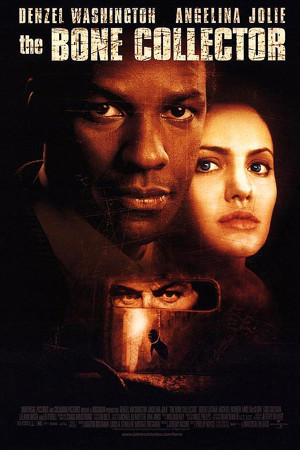

THE BONE COLLECTOR MOVIE REVIEW |

FEO AMANTE'S HORROR THRILLERCreated by:E.C.McMullen Jr. FOLLOW ME @ |

| Amazon |

| ECMJr |

| Feo Blog |

| IMDb |

| Stage32 |

| X |

| YouTube |

| Zazzle Shop |